Learn Some Valuable Lessons From Ancient Greek Coinage

2017-12-14 Thu

The Athens exhibition links money with its users’ inner lives and has it all, from Alexander the Great’s monetary modesty to the savings of prostitutes.The Greek word for money, chrema, carries a significance its English translation cannot fully convey. “It means ‘to need’ and ‘to use’ together,” explains Nicholas Stampolidis, director of the Museum of Cycladic Art (MoCA) during a recent visit to the museum’s latest exhibition, “Money: Tangible Symbols in Ancient Greece.”

Technology is spread out everywhere, payments are deposited into online bank accounts. People can spend weeks without exchanging paper notes or metal coins. Even basic transactions are relegated to plastic cards, wire transfers and perhaps bitcoin. In both senses of chrema, people need and use money more than ever; it’s hard to imagine trading a bushel of wheat or a jug of olive oil for a pair of trainers or mobile-phone service. Exploring the tangibility of currency is what makes “Money” such a fascinating exhibit.

The Athenian museum, in partnership with Alpha Bank Numismatic Collection, is displaying 85 ancient coins from around the Mediterranean basin, Asia Minor and Central Asia. The coins, which date as far back as the 7th century BC, are complemented by 159 artefacts such as vases, jewellery, perfume bottles, and statuettes, on loan from 32 different archaeological collections in Europe, including the British Museum and the Louvre.

However, things are not as easy for the curators because they have to ensure that public engagement with coins should be there. The viewer can get bored once he sees the organized set of coins in metal type, therefore a simple timeline would be there to highlight the changes over time. Instead, Mr. Stampolidis decided to showcase the holistic nature of money by structuring the exhibit around eight units: transactions, trade, art, history, circulation of ideas, propaganda, society, and banks. By connecting artefacts with coins, the exhibit allows the visitor to explore the link between money and the people who used it.

Ancient coins are designed mostly by artists and sculptors and carry messages of the ancient world.

The first Greek coin, produced on Aegina Island, is stamped with a sea turtle—chosen because it was the longest-living animal the islanders knew of. A linear inscription of an incuse square divided into five sections decorates the coin’s backside. The same inscription is now the logo of Alpha Bank, Greece’s largest bank. Oenology, a vital part of ancient Grecian society, is equally represented: an 8th-century-BC black pile of carbonised grapes excavated in Crete sits next to a silver drachm (a type of coin) stamped with a grapevine, heavy with fruit. The exact same icon is seen imprinted on the handles of several wine jugs.

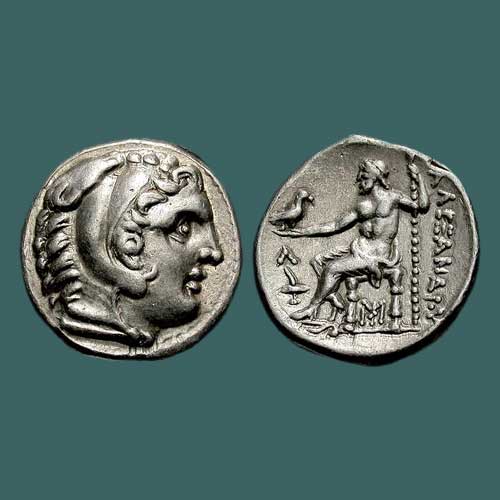

Since many centuries, rulers created their own unique symbols on coins to propagate a flattering image or favoured ideas. What was omitted was just as symbolic. During Alexander the Great’s reign, his profile remained notoriously absent from any coin. A pupil of Aristotle, who warned against hubris, Alexander put the ancient gods on his coins instead. His successors were eager to draw parallels between their own rule and the great emperor. Alexander’s head was dutifully stamped next to a slew of emperors’ names as far away as Bactria, in what is today’s northern Afghanistan.

The old adage “money can’t buy happiness” seems to be thrown out the window in the “Society" unit. In the first century BC, the port town of Delos was a tax haven, attracting sea-faring merchants. In 1991, an excavation of a local tavern reveals ancient hedonistic secrets, among the display of broken wine jugs sits a pile of coins with markings from dozens of different societies—the savings of prostitutes after servicing clients from around the world.

A short summary is given to the precursors of ancient Greek money: barter trade, livestock heads, and metal lumps, which eventually gave way to metre-long spits called obeloi. The average male hand could grab six obeloi; a unit of six was called a drattomai. The word evolved to drachma, the name of Greece’s currency before the euro.

Some viewers might be tempted to draw comparisons with modern Greece's financial woes. But today?s money has changed beyond recognition: the European Central Bank “prints” money—actually creating it without physically printing it—to buy bonds. Millions of dollars are “traded” across financial markets in a hundredth of a second. These and other monetary machinations are so distant and abstract they make “money” seem meaningless. But in the ancient world, money was reassuringly tangible. Gold, even melted down, was still gold—a quality that made many believe it was magical. That certainly didn?t prevent inflation and financial panics, which the ancient Greeks suffered. But these beautiful coins and their human details—flexing athletes and laurels—recall a time when money, at least, was something people felt they understood.

Latest News

-

Gold Pagoda of Vijaynagar Empire King Deva Raya I

2024-04-10 WedKing Deva Raya I of the Vijayanagara Empire was a patron of Kannada literature and architecture. He ...

-

Silver Denarius of Septimus Severus

2024-04-05 FriLucius Septimius Severus served as the Roman emperor from 193 to 211 AD. Severus sat on the throne o...

-

Extremely rare 'Malaharamari' type Gold Gadyana of King Guhalladeva-III Sold for INR 611000

2024-04-03 WedTribhuvanamalla, also known as Guhalladeva III, was the ruler of the Kadamba dynasty. His reign coin...

-

90 Years of RBI

2024-04-02 TueOn 1st April, PM #Modi unveiled a special commemorative coin marking 90 Years since the foundation o...

-

Silver Denarius of Julia Mamaea

2024-04-02 TueJulia Avita Mamaea, a Christian Syrian noblewoman, was the mother of Roman Emperor Alexander Severus...